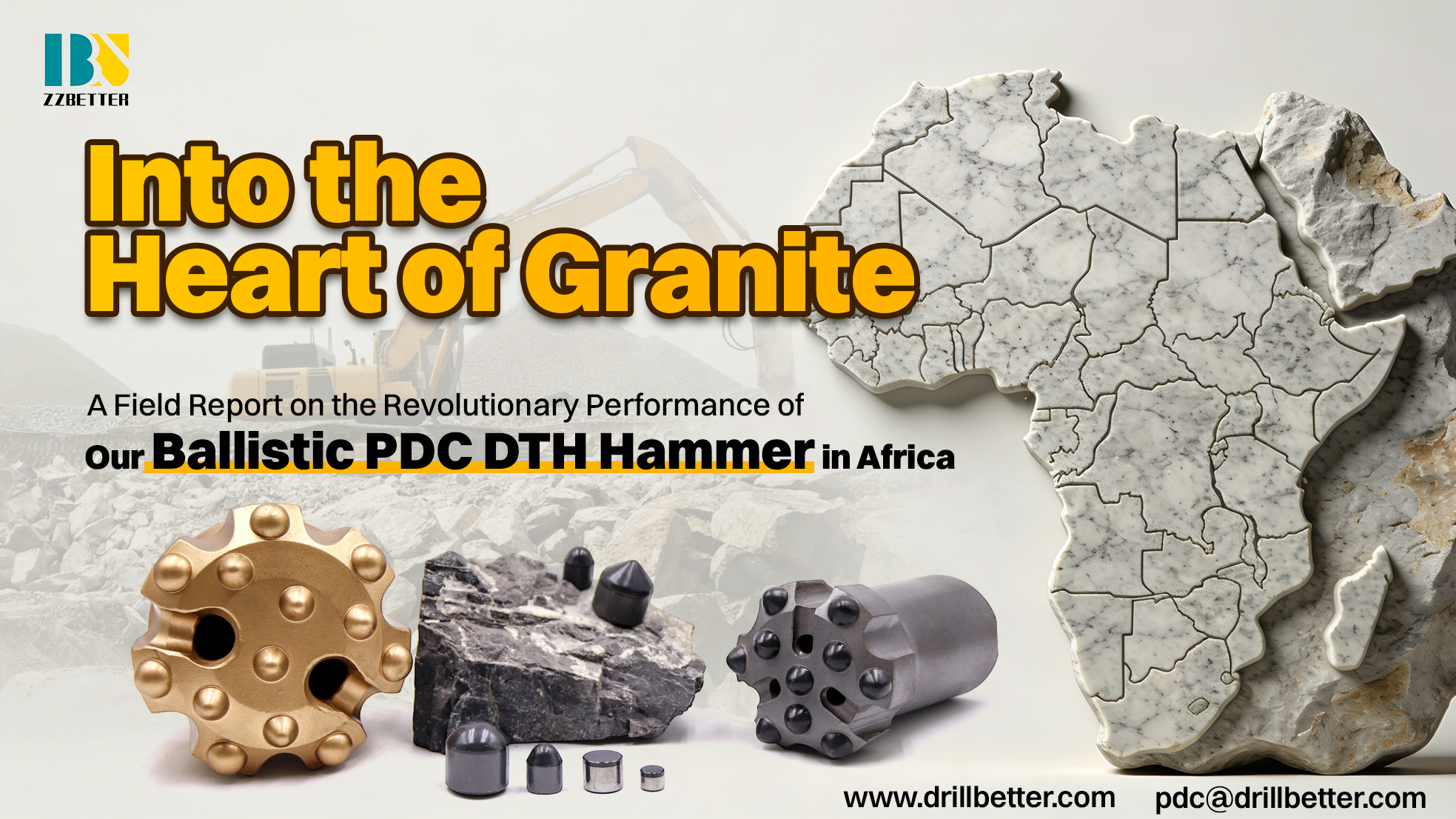

The remarkable achievement of a new PDC drill bit delivering a 50.9% increase in Rate of Penetration (ROP) in Algeria is far from a simple case of harder materials. It is a masterclass in the critical importance of precision PDC cutter design. This breakthrough underscores a fundamental truth in modern drilling: success is not just about having diamond cutters, but about deploying the right cutter geometry, structure, and configuration for the specific rock mechanics at hand. Understanding this symbiosis between design and formation is key to unlocking unparalleled efficiency.

The Pivotal Role of PDC Cutter Design

A PDC cutter is a sophisticated engineering component, and its design directly influences its rock-breaking mechanism. Key design elements include:

●Geometry: This is the shape of the cutter face (e.g., cylindrical, conical, parabolic, asymmetric). A sharp, pointed geometry excels at fracturing hard, brittle rock by concentrating point-load stresses. In contrast, a rounded or flat geometry is better for scraping and shearing through softer, ductile formations.

●Interface Structure: The bond between the diamond table and the carbide substrate is a common failure point. Advanced designs feature non-planar, wave-like, or stepped interfaces that massively increase interfacial area and strength. This dramatically improves impact resistance, preventing the diamond table from chipping or delaminating in hard, interbedded formations—precisely the challenge faced in Algeria.

●Size and Orientation: Larger cutters provide greater wear volume for abrasive formations, while smaller cutters can be densely packed for aggressiveness. The back rake (tilt) and side rake angles determine how the cutter engages the rock; a more negative rake angle enhances durability but requires higher weight-on-bit.

Matching Cutter Design to Formation Type

Selecting the correct PDC design is a science of matching the tool's strengths to the formation's weaknesses

1.Soft to Medium, Abrasive Formations (e.g., shales, clays, soft sandstones):

Design Priority: Wear resistance, cleaning, and thermal stability.

Ideal Cutter: Sharp, planar geometry with a high degree of thermal stability. The focus is on maximizing footage drilled by resisting abrasive wear. Efficient bottom-hole cleaning is crucial to prevent balling.

2.Hard, Abrasive, and Interbedded Formations (e.g., the Algerian case, hard sandstones, siltstones):

Design Priority: Impact resistance, durability, and thermal fatigue resistance.

Ideal Cutter: Robust, non-planar interface design (e.g., Axe-Blade, Deep Reef style) with a strong, shock-resistant substrate. A slightly more negative rake angle enhances durability. These cutters are engineered to withstand the violent shocks from hitting hard stringers without failing.

3.Very Hard and Ultra-Abrasive Formations (e.g., chert, pyrite, quartzite):

Design Priority: Extreme impact and abrasion resistance.

Ideal Cutter: Specialized geometries like conical or chisel-shaped elements. These are designed to point-load and micro-fracture the rock rather than shear it. They often trade off some aggressiveness for supreme survivability.

A Framework for Client Selection: How to Choose the Right PDC Cutter

For clients, navigating this complex landscape requires a structured approach based on data and collaboration:

●Analyze Offset Well Data: The most critical step. Review drilling logs from nearby wells to identify the specific formation layers that caused issues: slow ROP, severe vibrations, or premature bit wear. This history reveals the primary challenge—is it abrasiveness, impact, or both?

●Define the Primary Drilling Objective: Is the goal to drill faster (maximize ROP), drill longer (maximize footage), or simply to ensure the bit completes the section without failure (maximize reliability)? The answer will guide the trade-off between aggressiveness and durability.

●Collaborate with Bit Manufacturers: Engage in technical discussions with bit design engineers. Present your formation data and objectives. Reputable manufacturers use advanced modeling software to simulate cutter-rock interaction and can recommend a cutter technology portfolio tailored to your specific well profile.

●Evaluate the Total Cost per Foot: The choice should not be based on bit cost alone. A more expensive bit equipped with premium, application-specific cutters that drill faster and longer will almost always yield a significantly lower cost per foot than a standard bit that fails prematurely or drills slowly.

The Algerian record is a powerful testament to this philosophy. It was achieved not by chance, but by applying a cutter design specifically engineered to conquer the local formation's challenges. For the industry, the lesson is clear: strategic investment in the right PDC technology, selected through rigorous analysis and collaboration, is the most direct path to radical performance improvement and operational savings.